Infographic made with NotebookLM by feeding it this post. No further prompts.

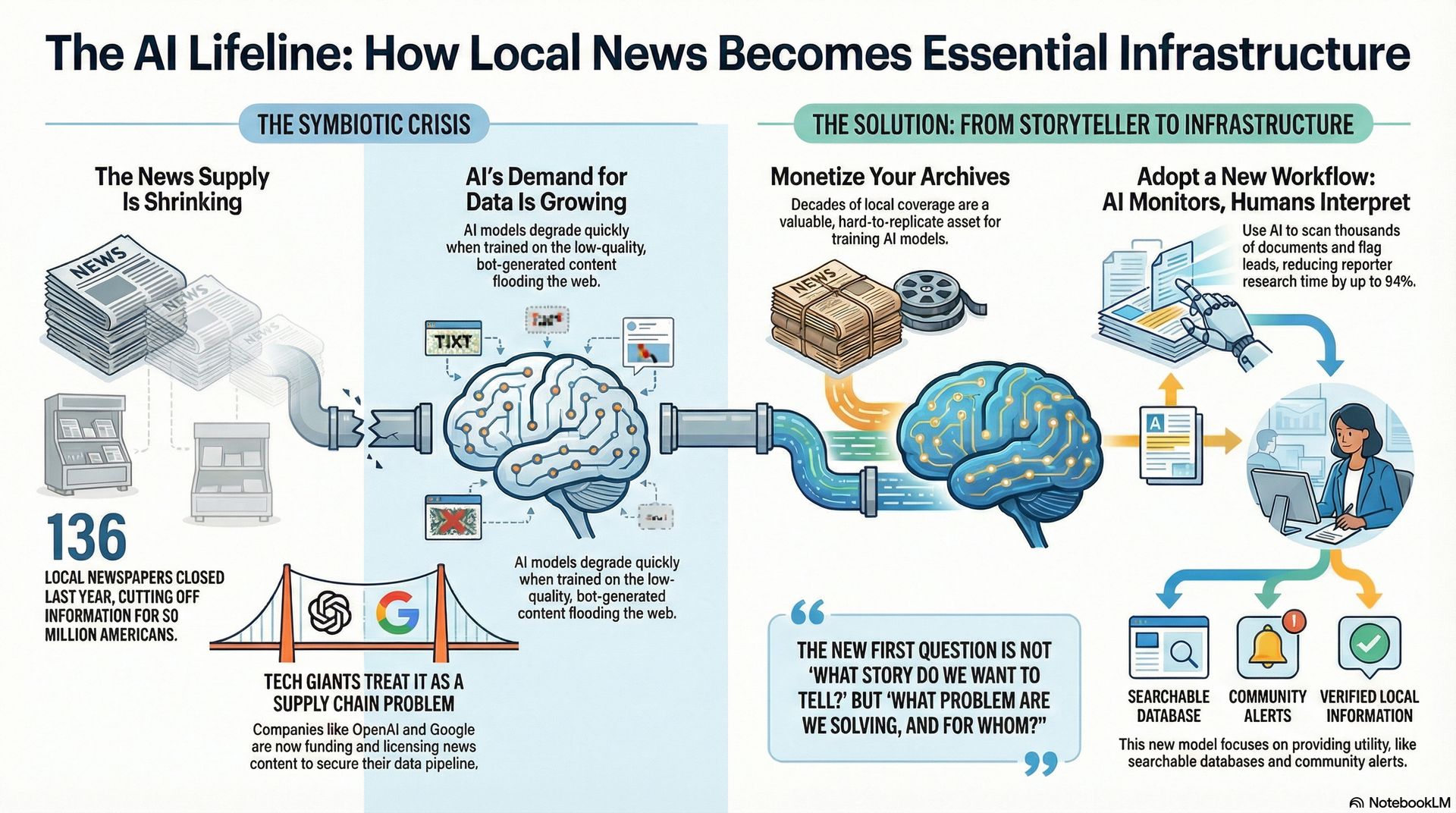

AI models can only remain accurate if they ingest a steady stream of fresh, verified, human-reported information. But the supply of that information, especially local reporting, is collapsing. The Medill State of Local News Report 2025 tracked 136 newspaper closures last year - more than two per week - pushing the number of news desert counties to a record 213. Some 50 million Americans now have limited or no access to local news. Just last week, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette announced that it will cease operations in May, which would be the first major metropolitan newspaper closure since the Tampa Tribune in 2016.

Meanwhile, the open web is filling with AI-generated slop, bot-made news sites, and SEO spam. Models trained on that material degrade quickly. And no trillion-dollar AI company can tolerate that risk.

Jennifer Brandel (Hearken CEO, Stanford JSK Fellow) lays out the implications in her Nieman prediction for 2026: AI companies are already paying some news organizations to safeguard the information supply their models depend on. She predicts 2026 will be when they start building networks of reporters or buying news outlets outright.

Some early moves: OpenAI is funding Axios Local's expansion. Google is bankrolling California local news efforts. Microsoft partnered with Semafor. Major licensing deals are stacking up with AP, Axel Springer, Financial Times and News Corp.

These are not philanthropy but supply-chain decisions. When a critical input becomes unstable, corporations vertically integrate.

This creates an opening for local news organizations, but also a question: What happens when the largest consumers of journalism are also its funders?

Archives as leverage

Derek Willis (University of Maryland) argues in his Nieman prediction that local archives contain information "prohibitively expensive for tech companies to recreate": not just stories, but legal notices, event calendars, obituaries, high school sports statistics. His students working with a Maryland newspaper's archive found details they could not locate anywhere else.

The implication: Local newsrooms have been sitting on assets without realizing their value. In my report "The Human-Augmented Newsroom", I document how some news organizations are starting to activate those assets.

The Philadelphia Inquirer built a vector database of 200 years of coverage, enabling conversational queries across the archive. The Baltimore Banner used AI classification on 15,000 articles and discovered that human-centric stories drove subscriptions while policy coverage underperformed—a finding that prompted editorial reallocation. On a national level, The Wall Street Journal's Lars chatbot, a WSJ-branded AI tax assistant designed to answer readers’ U.S. tax questions, handles 9,000 monthly subscriber conversations drawn from archived tax coverage.

These applications share a pattern: They apply AI to well-defined problems with verifiable outputs. Semantic search and classification deliver benefits without the accuracy risks of content generation.

Willis makes a key point about what this requires: Archives need to be treated as "a first-class product of the newsroom, not a byproduct of it." Most local newsrooms have never had reason to think this way. Now they do - both for internal value (searchable context, faster onboarding, editorial intelligence) and external leverage (licensing revenue from companies that need accurate local training data).

From storage cost to community utility

But the bigger shift is not just monetizing archives. It is rethinking what a local news organization does.

In 2006, Adrian Holovaty published a groundbreaking essay arguing that local journalists collect structured information every day (fires, permits, court cases) and then bury it in prose that cannot be searched or reused. Six years later, Jeff Jarvis made the same point from a personal perspective after Hurricane Sandy. He needed to know about passable streets and working gas stations. His local outlet gave him stories. "Don't give me stories," he wrote. "Give me lists."

Both arguments circulated for years without changing much. Most local newsrooms lacked the developers and budgets to build infrastructure. AI changes the economics. Tools that once required dedicated R&D now work through a Slack integration.

The pioneers I've been documenting share a model: AI monitors volume (government meetings, court filings, municipal documents), humans interpret and report. iTromsø in Norway built DJINN, scanning 12,000 municipal documents monthly—94 percent reduction in research time. CT Mirror monitors 169 Connecticut towns, flagging anomalies for beat reporters. Village Media in Canada licenses its government-monitoring tools to over 100 publishers.

What distinguishes these projects is that they change the relationship between newsroom and community. Village Media's board chair Richard Gingras told me they no longer see themselves as a media company but as a "community impact organization." Their platform lets residents follow local topics the way Reddit does. The newsroom becomes infrastructure.

Eric Ulken (former Baltimore Banner, Stanford JSK Fellow) frames the shift precisely in his Nieman prediction: "The new first question is not 'What story do we want to tell?' but 'What problem are we solving, and for whom?'"

This is not abandoning journalism but recognizing that audience service earns the trust that makes public-service journalism possible. Local news bundles lost their practical benefits years ago (remember TV listings?) without replacing them. The infrastructure model fills that gap.

One caveat matters. Research from Trusting News shows audiences react negatively when they learn AI was used in news production, even with humans in the loop. The Medill Local News Survey 2025 found 47 percent comfortable with AI-assisted journalism but only 17 percent comfortable with AI-produced content.

The successful implementations thread this needle by using AI to process, not produce. They maintain human judgment at decision points. And they are transparent about what AI does and what journalists do.

What this means for local newsrooms

Three practical takeaways:

Audit what you have. Often, newsrooms do not know the state of their archives: digitization, metadata quality, rights ownership. This is a prerequisite to everything else.

Start with document processing. The highest-value, lowest-risk applications involve structured data that humans then interpret. Monitor meetings. Track filings. Generate leads, not stories.

Think service. Jarvis's 2012 question still applies: What do people in your community actually need during a crisis, an election, a housing crunch? Sometimes the answer is a searchable database or an alert when something changes. The story can come later.

The next time a hurricane hits, residents in forward-thinking communities will know which gas stations have fuel and which roads are open - not from articles, but from infrastructure their local newsroom built. Twenty years after Holovaty described the vision, the tools finally exist.

Archives and local infrastructure are two of five strategic patterns in my report, "The Human-Augmented Newsroom: AI in Journalism Strategic Patterns 2025." The full report includes action roadmaps, business model patterns, and sections on reader-facing AI and authenticity as competitive advantage. [Available to paid subscribers.]